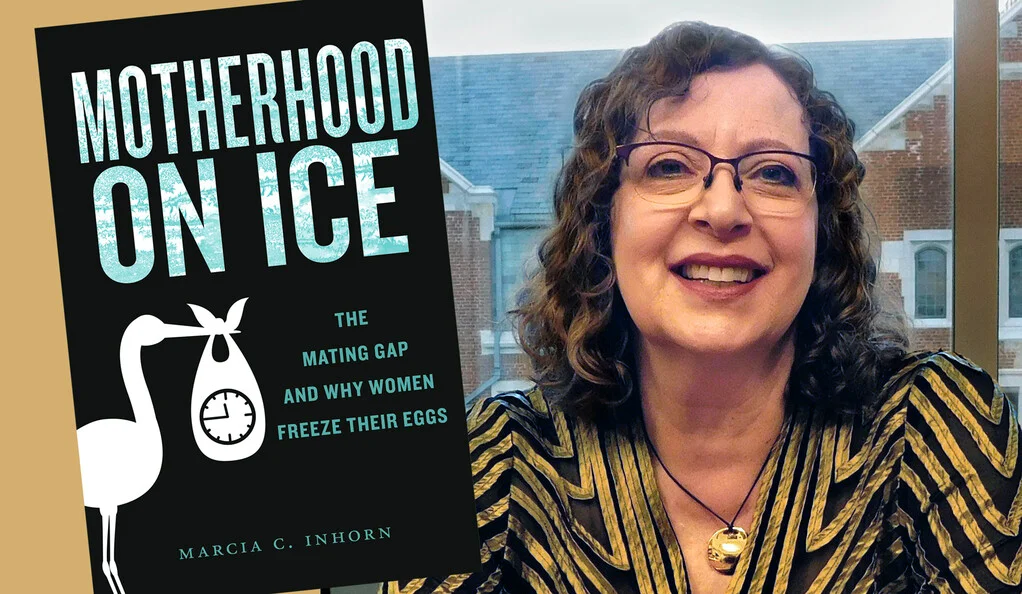

Marcia C. Inhorn, PhD, MPH, is the William K. Lanman, Jr. Professor of Anthropology and International Affairs in the Department of Anthropology and The Whitney and Betty MacMillan Center for International and Area Studies at Yale University, where she serves as Chair of the Council on Middle East Studies. A specialist on Middle Eastern gender, religion, and health, Inhorn has conducted research on the social impact of infertility and assisted reproductive technologies in Egypt, Lebanon, the United Arab Emirates, and Arab America over the past 35 years. She is the author of six books on the subject, editor or co-editor of thirteen volumes, founding editor of the Journal of Middle East Women’s Studies (JMEWS), and co-editor of the Berghahn Book series on “Fertility, Reproduction, and Sexuality.” Inhorn has received more than a dozen awards for her books and scholarship, and along with her colleague Sarah Franklin of Cambridge University, is the recipient of a major Wellcome Trust Foundation grant for a global project on “Changing (In)Fertilities.”

Inhorn’s newest book, Motherhood on Ice: The Mating Gap and Why Women Freeze Their Eggs (NYU Press, 2023) draws upon interviews with more than 150 American women to explore their use of egg freezing as a fertility preservation technology. Their stories show that, contrary to popular belief, egg freezing is rarely about women postponing fertility for the sake of their careers. Rather, the most-educated women are increasingly forced to delay childbearing because they face a mating gap—a lack of eligible, educated, equal partners ready for marriage and parenthood. For these women, egg freezing is a reproductive backstop, a technological attempt to bridge the gap while waiting for the right partner. But it is not an easy choice for most. Their stories reveal why egg freezing is logistically complicated, physically taxing, financially demanding, emotionally draining, and uncertain in its effects. Yet, for many “thirty-something” women, egg freezing offers the future hope of partnership, pregnancy, and parenthood.

She has served as president of the Society for Medical Anthropology (SMA), and director of Middle East centers at both Yale University and University of Michigan. Inhorn is also the recipient of a National Science Foundation grant for her project on oocyte cryopreservation (egg freezing) for both medical and elective fertility preservation. This is the topic of her next book, as well as a series of scholarly and media articles.

Announcements

Motherhood on Ice: The Mating Gap and Why Women Freeze Their Eggs

NYU Press, May 1, 2023

“Extremely rich in nuanced analysis, Motherhood on Ice vividly portrays the experiences of women—of various racial and religious backgrounds—at every stage of this oftentimes fraught process. Inhorn addresses a critical societal issue with conviction and grace.” Chantal Collard, Concordia University

“Passionate, empathic, and rigorously researched, this book will be popular amongst audiences ranging from single, well-heeled thirty-something professional women considering egg freezing to public health, medical anthropology, and gender studies academic audiences.” Rayna Rapp, Professor Emerita of Anthropology, New York University

“Simply outstanding. This book will surely garner attention and cultivate widespread appeal.” Rosanna Hertz, author of Random Families: Genetic Strangers, Sperm Donor Siblings and the Creation of New Kin

Why are women freezing their eggs in record numbers? Motherhood on Ice explores this question by drawing on the stories of more than 150 women who pursued fertility preservation technology. Moving between narratives of pain and empowerment, these nuanced personal stories reveal the complexity of women’s lives as they struggle to preserve and extend their fertility.

Contrary to popular belief, egg freezing is rarely about women postponing fertility for the sake of their careers. Rather, the most-educated women are increasingly forced to delay childbearing because they face a mating gap—a lack of eligible, educated, equal partners ready for marriage and parenthood. For these women, egg freezing is a reproductive backstop, a technological attempt to bridge the gap while waiting for the right partner. But it is not an easy choice for most. Their stories reveal the extent to which it is logistically complicated, physically taxing, financially demanding, emotionally draining, and uncertain in its effects.

In this powerful book, women share their reflections on their clinical encounters, as well as the immense hopes and investments they place in this high-tech fertility preservation strategy. Race, religion, and the role of men in the lives of single women pursuing this technology are thoroughly explored. A distinctly human portrait of an understudied and rapidly growing population, Motherhood on Ice examines what is at stake for women who take comfort in their frozen eggs while embarking on their quests for partnership, pregnancy, and parenting.

Marcia C. Inhorn is the William K. Lanman, Jr. Professor of Anthropology and International Affairs at Yale University and author of Cosmopolitan Conceptions: IVF Sojourns in Global Dubai.

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS

Washington Square

New York, NY 10003

Media Interviews and Podcasts for Motherhood on Ice:

- “Your Boss Will Freeze Your Eggs Now,” The New York Times, June 29, 2024.

- “Kinderwunsch Auf Eis,” (Child Desire on Ice),” SonntagsBlick, May 26, 2024.

- “Giving Myself the Best Opportunity at Motherhood: Why More Aussie Women Are Undergoing This Procedure,” The Weekend, May 26, 2024.

- “Does the Biological Clock Still Matter?“, May 22, 2024, The Midst.

- “Book Review: Motherhood on Ice—The Mating Gap and Why Women Freeze Their Eggs,” Progress Educational Trust, April 29, 2024.

- “The Failed Promise of Egg Freezing,” April 29, 2024, Vox.

- “Why Do Some Women Regret Freezing Their Eggs?“, The Cut, April 2, 2024.

- “A Look at Why Many Women Undergo Egg Freezing and the Costs Associated with It,” CNBC, March 30, 2024.

- “The Promise and the Perils of the Egg-Freezing Revolution,” The Financial Times, March 23, 2024

- “Interview with Dr. Marcia Inhorn on Her Book Motherhood on Ice,” By Radell Peischler, Fertility Boss, March 8, 2024.

- “More Women Than Ever Are Freezing Their Eggs. But There’s a Problem.” The Boston Globe, February 6, 2024.

- “Sophie Michot Only Meets Men that Want to Party. Researchers Are Seeing a Troubling Trend.” Aftenposten Norway, February 3, 2024.

- “Stop the Time. More and More Women Are Freezing Their Eggs to Pause Their Biological Clock.” Volkskrant, The Netherlands. February 3, 2024

- “Egg Vitrification: Exploring the Social and Psychological Impacts of Egg Freezing,” Finding Genius Podcast with Richard Jacobs, November 24, 2023,

- “Why Aren’t More People Marrying? Ask Women What Dating is Like.” New York Times, November 11, 2023.

- “Women Are Freezing Their Eggs Because They Can’t Find a Partner”: Marcia Inhorn, Anthropologist at Yale University,” Una Mama Millennial, October 31, 2023.

- “Women Freeze Their Eggs Because They Cannot Find a Suitable Partner,” Der Standard, October 17, 2023.

- “Single Moms Know Marriage Would Be Ideal, But How Do They Get One?,” Opinion by Christine Emba, The Washington Post, September 28, 2023.

- “What the Egg-Freezing Process Feels Like: One Woman’s Fertility Journey,” Perspective by Matilda Hay, The Washington Post, September 25, 2023.

- Motherhood on Ice: The Mating Gap and Why Women Freeze Their Eggs, The Missing Piece Podcast by Will, Taiwan September 23, 2023.

- “Growing Infertility,” 360 News with Scottie Nell Hughes, September 18, 2023.

- “Why Are Women Freezing Their Eggs? Look to the Men,” The Atlantic, Book Review By Anna Louie Sussman, September 14, 2023.

- Motherhood on Ice: The Mating Gap and Why Women Freeze Their Eggs, Reviewed by Randi Hutter Epstein, Yale Alumni Magazine, September-October 2023.

- “The Real Reason that Women are Freezing Their Eggs: The Mating Gap,” Quiet the Clock Podcast Hosted by Beth Gulotta, Episode 21, August 30, 2023.

- Amplifying Women’s Egg Freezing Journey: Learning and Necessary Changes with Marcia Inhorn, Quiet the Clock, Podcast Hosted by Beth Gulotta, Episode 20, August 23, 2023.

- Women Should Mix with Less Educated Men (in German), Falter (Austria), Article by Lina Paulitsch, August 22, 2023.

- Most women freeze their eggs because of partnership issues, The Hill, July 28, 2023

- The Page 99 Test: Motherhood on Ice, July 21, 2023

- What’s changing about childbirth?, BBC Radio, June 19, 2023.

- The Mating Gap and Why Women Freeze Their Eggs with Author/Professor Marcia Inhorn, Girls Gotta Eat Hosted by Rayna Greenberg & Ashley Hesseltine, Apple Podcast, June 4, 2023.

- Motherhood on Ice, Faculti, May 31, 2023.

- Why Women Freeze Their Eggs with Professor Marcia C. Inhorn, Ask a Matchmaker with Maria Avgitidis, Apple Podcast, May 30, 2023.

- ‘Motherhood on ice’: Exploring why women freeze their eggs, Yale News, May 9, 2023.

- Motherhood on ice: lack of suitable men drives women to freeze their eggs, The Guardian, April 23. 2023.

- It’s not about career planning. As a medical anthropologist, I can tell you that women are freezing their eggs because of partnership problems, INSIDER, March 20, 2023.

‘Motherhood on Ice’: Exploring Why Women Freeze Their Eggs

Oocyte vitrification, a method to flash-freeze human eggs so they can be stored for later use, emerged in the early 2000s. Initially, the technology was limited to women undergoing chemotherapy or experiencing medical conditions known to cause infertility.

In 2012, the American Society for Reproductive Medicine lifted the procedure’s experimental label, allowing women to freeze their eggs for non-medical reasons. By the end of 2019, more than 36,000 women in the United States used the increasingly popular technology to preserve their eggs and extend their fertility.

What drives them to this decision?

In a new book, “Motherhood on Ice: The Mating Gap and Why Women Freeze Their Eggs” (New York University Press), Yale anthropologist Marcia C. Inhorn explores the factors that motivate different individuals to freeze their eggs — including what she describes as a “mating gap” causing a shortage of partners for college-educated women — that run counter to popular assumptions.

Her narrative, drawn from interviews with 150 women who underwent the procedure, reveals the real-world complexities behind women’s choices.

In an interview with Yale News, Inhorn, the William K. Lanman Jr. Professor of Anthropology and International Affairs in Yale’s Faculty of Arts and Sciences, discusses what she found and how it runs counter to the conventional wisdom about egg freezing’s rising popularity. The interview is condensed and edited.

What inspired you to write this book?

Marcia C. Inhorn: Ever since egg freezing became available for reasons beyond medical conditions, there has been a lot of discussion about who is using this technology. The common assumption is that most women who freeze their eggs are twenty-somethings who want to delay childbirth in consideration of their career trajectories. They want to put motherhood on hold as they pursue their careers and egg freezing is a way of keeping their options open.

I thought this assumption was worth investigating. Perhaps there was an alternative hypothesis that we hadn’t been discussing. Thirty-six of the women I interviewed had frozen their eggs for medical reasons. The book focuses on the stories of the 114 women who froze their eggs for non-medical reasons.

What did you learn?

Inhorn: Overwhelmingly, the women who froze their eggs electively were in their thirties and motivated by partnership problems. Eighty-two percent of them were single and being single was why they froze their eggs. That’s my big finding and it runs against popular conceptions of the young professional woman who is so busy with her career that she wants to put off having kids.

These are well-educated and successful women who found themselves in the difficult situation of wanting partnership, pregnancy, and parenthood, but are unable to find a suitable reproductive partner. They are lacking what I call the “three Es” in potential partners: eligible, educated, and equal.

Women’s fertility starts to significantly decline at 37, which is called the “fertility cliff.” The women I interviewed were at or near the cliff. They want to be mothers but feel that time is running out. The book humanizes the women who find themselves in this difficult situation.

Why are so many educated and successful professional women struggling to find partners?

Inhorn: Some of the women I interviewed said they knew other women in the same situation as them. They believed that something must be happening demographically. They’re right. In big cities across the country, there are more college-educated women than men. It’s the underlying explanation for what I call the mating gap, which is driving the increasing popularity of egg freezing.

An economic journalist named Jon Birger published a book in 2015 called “Date-onomics” that informed my research. He used census data to analyze the educational disparities between men and women in the United States, which have been growing since the 1980s. Women are matriculating and graduating from four-year universities and colleges at a significantly higher rate than men. Simultaneously, men are sliding out of higher education. Birger calls this the “man deficit,” a massive undersupply of college-educated men and a significant oversupply of college-educated women.

I also looked at World Bank statistics, something called the Gender Parity Index, which looks at this education deficit between men and women. Women are outstripping and outperforming men in higher education in more than 60% of the world’s countries.

Are men simply reluctant to enter relationships with women who are more educated and successful than them?

Inhorn: That was among the issues the women discussed with me. They said that men feel intimidated being with someone who is better educated, more accomplished, or makes more money than they do. At the same time, successful women tend to want to find partners who are equally educated and accomplished. They often told me about their experiences with online dating and how men seemed to be intimidated by their success. Women said they knew they’d get nowhere if they disclosed that they had a Ph.D. on their online dating profile.

They mentioned other issues, too. The most prevalent being men’s general lack of readiness or willingness to marry and become fathers. A lot of men are single at heart. Women called them “Peter Pans” because of their reluctance to grow up. They might be educated and professionally successful — they may wine and dine you — but they have no intention of settling down. The book includes poignant stories of women who loved these men and wanted to be with them and have children, but the guys just couldn’t get there.

I should note that I don’t condemn men in this book. There is a chapter where I discuss the important role men play in the lives of women who decide to freeze their eggs. Fathers, brothers, male friends, sometimes even women’s ex-partners support them.

What is the process for having eggs frozen?

Inhorn: It is not an easy proposition. I have a full chapter on the logistical difficulty of doing it. Minimally, it costs about $10,000 to do one cycle of egg freezing, but it often ends up costing much more because of the hormonal medications needed. You need to self-inject hormonal medications, which is very trying, and the hormones are expensive. The cost can wind up being closer to $15,000 per cycle.

Inhorn: It’s not a solution to the mating gap, but egg freezing is a bridging technology to help women to buy a little time at the end of the reproductive lifespan. It can function as a sort of reproductive backstop. If you find yourself without a partner but really wanting to be a mom of your own bio-genetic children, then you should consider egg freezing if you have the money to do it. I’m not advocating egg freezing, but I am arguing it is a tool that one should consider, particularly for single women in their thirties who know they want to become mothers.

Unless the mating gap is corrected swiftly, and a lot more men start graduating college, the gap will continue growing. In anthropology we have these terms “hypergamy” and “hypogamy.” Hypergamy is marrying up. Hypogamy is marrying down. Traditionally women have engaged in hypergamy, marrying somebody slightly older, better educated, who maybe makes more money. Today, women who are highly educated and successful are facing a lack of potential male partners with similar levels of education or professional success. Perhaps they need to consider hypogamy. That doesn’t mean they should settle for someone below their standards. But if a person makes you happy and is kind to you, you can have a great relationship.

And similarly, men are going to have to overcome their intimidation of highly educated and successful women. They need to realize that it’s wonderful to be in a committed relationship with somebody who is well educated and successful.