By Mike Cummings

Millions of people visit Dubai each year on business and for pleasure. While Dubai has emerged as a global hub city for commerce and tourism, it also is becoming an international center for medical care, including in vitro fertilization (IVF). People who cannot access safe, affordable, or effective IVF services in their home countries travel to Dubai by the thousands on a desperate quest to conceive.

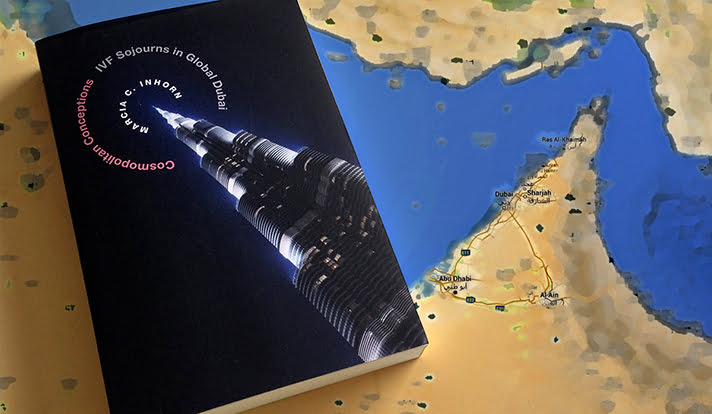

Marcia C. Inhorn, the William K. Lanman Jr. Professor of Anthropology and International Affairs, describes the experiences of reproductive travelers in her latest book, “Cosmopolitan Conceptions: IVF Sojourns in Global Dubai.”

The book features the voices of people Inhorn interviewed who had traveled to Dubai at great expense to seek IVF treatment. The stories of these “reprotravelers” provide insight into the frustration, pain, fear, and financial burden shouldered by those who are compelled to travel across borders for IVF services.

Inhorn recently spoke to YaleNews about her research.

What drives people to travel across borders for IVF treatment?

Reproductive travel is driven by a number of different factors, including resource shortages; legal, religious, and ethical barriers; quality of care issues; and cultural issues around privacy and cultural comfort.

The vast majority of the world’s people have no access to IVF. Many parts of the world just don’t have IVF technology yet. That’s the case in sub-Saharan Africa, which is a region that has some serious infertility problems, primarily caused by untreated tact infections, and a huge unmet need for IVF. Most Africans lack the economic means to travel for IVF treatment, but I did see African elites coming from the Horn of Africa — countries like Sudan, Ethiopia, Somalia — who were the moneyed people who could travel to Dubai.

Europeans were coming often to try to bypass laws. That’s probably the main driver in Europe. Each country has its own specific laws around IVF and people want to evade those laws. When they can’t get what they need in one country, they’ll go to another.

I saw people coming for quality of care issues. There were many people who had described to me medical horror stories. There were a lot of Indian couples who had experienced low-quality, horrible care and were fleeing their country to come to Dubai for what they saw as high-quality, safe, effective care.

The final category is socio-cultural considerations — people seeking treatment in a place where they feel comfortable. The clinic where I was performing my research in Dubai had an Indian doctor who was highly regarded for his quality of care and his cultural sensitivity, especially toward the problems faced by people from South Asia.

This kind of activity is often called “reproductive tourism.” Is that an appropriate term?

The people I interviewed were very critical of the term “tourism.” I had used the term in my study title because that was the common term in the literature. It was used on the flier that I posted on the clinic walls. People said, “Well, I’ve traveled, but I’m not a tourist.”

They said it is not leisurely; it is not fun; there is no vacation aspect to it. People often expressed desperation, especially people coming from cultural settings where it is almost mandatory to become a parent. They were feeling so stigmatized and under incredible social pressure to have children. I met people who had tried multiple IVF cycles in other places without success. They are traveling under pressure and they felt that “tourism” was making light of their journey.

I took their critique seriously. I revisited all the scholarship on this form of travel, and the word “tourism” is used over and over. In the introduction to my book, I make the point that we shouldn’t be perpetuating this term because it is inaccurate. In the book I use reproductive travel, and I shorten it to reprotravel.

You interviewed people who had traveled to Dubai for IVF care. What countries did they come from?

I conducted my study in a fertility clinic called Conceive that is located on the border with the neighboring emirate of Sharjah. I interviewed couples coming from 50 different countries. They were coming from some particular areas because of Dubai’s location on the eastern side of the Arabian Peninsula. There were patients from other Middle Eastern countries and there was a group of patients coming up the eastern coast of Africa, as well as from parts of South Asia: India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka. To my surprise, there were patients coming from Western countries; parts of Europe, Australia, even some Americans. They were coming to Dubai for a variety of reasons.

Did you sense desperation among the people you interviewed?

I really did. The United States is not the world’s most child-centered nation. Americans love their own children, but having children here is an option. You can choose not to have children and lead a perfectly normal and happy life. In other societies it is really considered to be culturally mandatory. When you get married, you’re expected to have children. The family expects it.

I started working in Egypt in the 1980s and I’ve worked in Lebanon and the United Arab Emirates. People in the Middle East not only want to have children, they need to have children. They tell you how much they adore children and they show it in their interactions with children. That desire for children — wanting that joy in your life and being expected to have children to keep your marriage viable — it does create a desperate feeling.

There’s been some critique of the “desperation narrative” in the search for IVF, but it is a discourse people use. They say they are desperate to have a child; that they try anything to avoid having any regrets. Coupled with that, it is difficult to adopt in a lot of countries; It’s not so easy in our country. In other societies, adoption is not considered an option at all. In the Middle East, legal adoption is not part of the Islamic religion.

What do you hope readers take away from the book?

What I first want people to realize is that infertility is a very important reproductive health issue. We don’t talk about it much, but some studies show that 10-15% of people in any given population are unable to have children. That’s a large percentage of people. I’d also like readers to understand that there is this global movement of people searching for reproductive technologies that they can’t get access to for one reason or another in their home countries.

This book is full of stories of people who have engaged in reproductive travel. They are stories of suffering. They are stories of hardship. They are stories of love. I feature 21 stories in the book to provide a portrayal of the humanity behind infertility, the searching and traveling, and the joy when IVF treatment succeeds and the suffering when it doesn’t.

The book is also very much about Dubai. It’s a different sort of place — one that is trying to brand itself as a cosmopolitan hub where people from any part of the world can come and feel comfortable. It is an unusually cosmopolitan part of the Middle East. You get a real sense of that from this book.

What can governments do to address the issues you raise in this book?

I argue that we need to do a lot more work to prevent the preventable forms of infertility, especially the infectious causes of infertility. This means better treatment of reproductive tract infections in women; better medical care so that women don’t end up getting infections through care; and smoking cessation among men to prevent infertility.

We need to provide better supports for infertile couples around the world so that people don’t feel so alone. We need to provide people other avenues so that they don’t feel so stigmatized by being infertile, especially for women. This means giving women options, like an education and a career, so they can have something fulfilling in their lives if they can’t have children.

Something that I emphasize in the book is a new movement called the low-cost IVF movement. It was started by some North American and European clinicians who argue that it is ridiculous that IVF is still so expensive and that we need to move low-cost IVF into parts of the world where people can’t currently afford it. A group in Belgium called The Walking Egg has developed a very low-cost form of IVF. It is like a mini-laboratory in a shoebox that is transportable. They are field-testing it right now in parts of Africa. It could deliver IVF for about $225. This would greatly reduce the need for people to travel for IVF.